- Gear Rentals

- Production Services

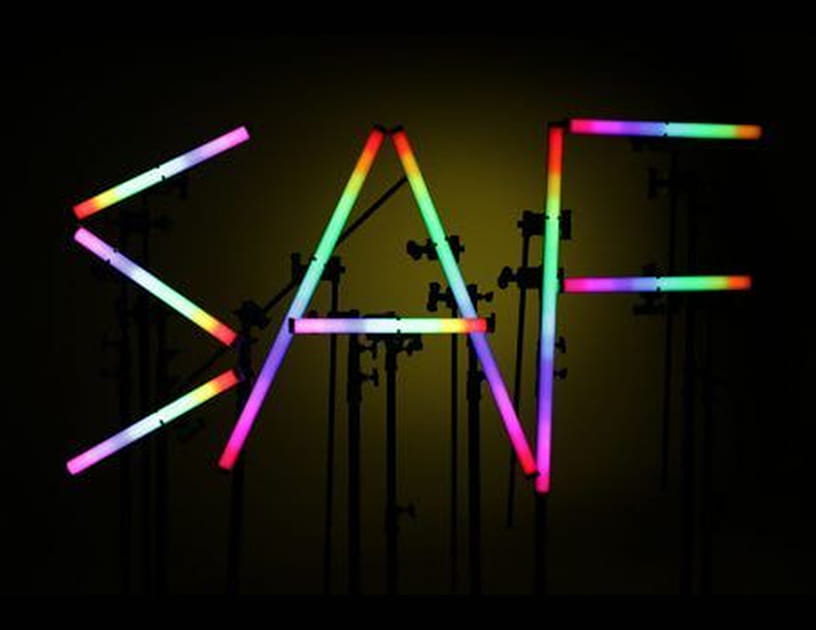

Stage Rental

The SAF Production Stage is a fully featured Cyc Soundstage rental located on the Westside of Los Angeles.

Stage Rental Policies

Professional Crew

From Director to Hair & Make Up Artist, Stray Angel Films have the crew you need for your production.

Production Services

- Events

- Stray Angel

- Contact Us